The Past, Present and Future of Black British Theatre

Join us on a journey through time as we explore Black British theatre—chronicling its retrospective roots and potential future.

It is not memory that fractured the legacy of Black British theatre—it was how these memories were stored. There are countless archives, books, and recordings of live performances that store crucial information about British theatre, stretching beyond Shakespeare and Marlowe's time. So why was Black British theatre forgotten?

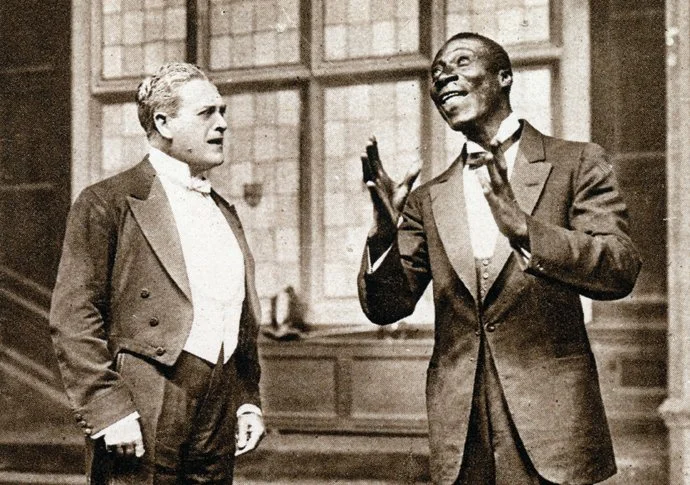

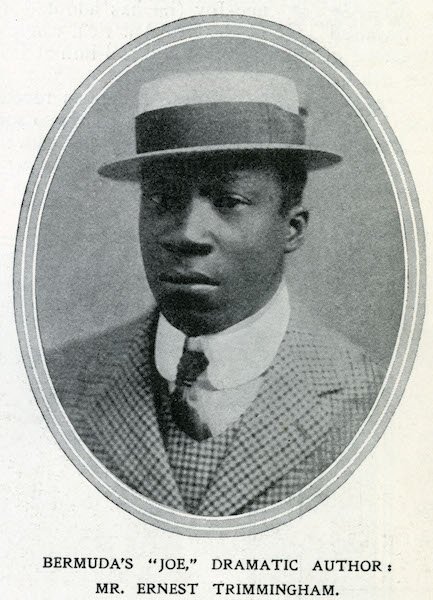

The National Theatre's Black Plays Archive was founded in 2013 and sought to respond to the archival gap. In a digital catalogue of over 850 plays written by more than 300 Black British, African and Caribbean playwrights, Ernest Trimmingham's plays are thought to be the earliest.

Trimmingham was a Bermudian immigrant and considered one of British cinema's first black actors. The Lily of Bermuda was staged in 1909 and co-written with Sudanese-Egyptian activist and playwright Duse Mohamed Ali. In 1932, The League of Coloured Peoples, a British civil rights organisation, sponsored the work of Uma Marson, one of the earliest Black women in British theatre.

Her standout four-act drama At What a Price follows Ruth Maitland, who must navigate racism and misogyny after moving to Kingston to work in the office of an English businessman. The Black Play Archives only records the work of Black British, African and Caribbean playwrights and actors, notably excluding African-Americans who performed on British stages.

Ira Aldridge's experiences of racism as an actor in America pushed him to emigrate to Liverpool, where he is remembered as one of the first Black stage actors in Britain. His most notable performances were in 1825 when he played Othello and Oroonoko. Subsequently, he was given the role of manager at Coventry Theatre Royal, a position he used to advocate for the abolition of slavery.

Kwame Kwei-Armah founded the Black Plays Archive project, and his work introduced me to the present world of Black British theatre. Kwei-Armah was born in West London to Grenadian parents and grew up around the corner from me in Southall in the 70s. His early childhood was marred by racism and ostracisation in our local area, and these experiences have influenced his work ever since.

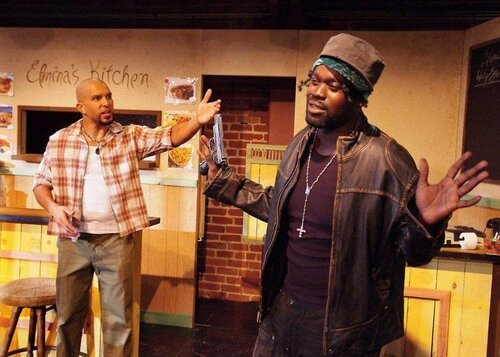

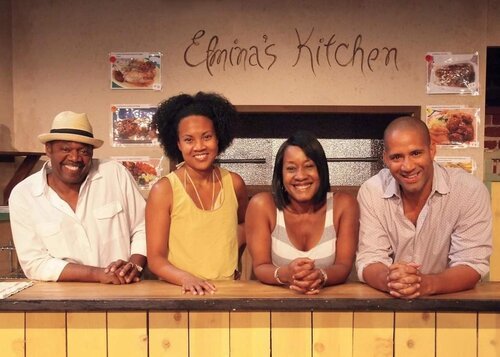

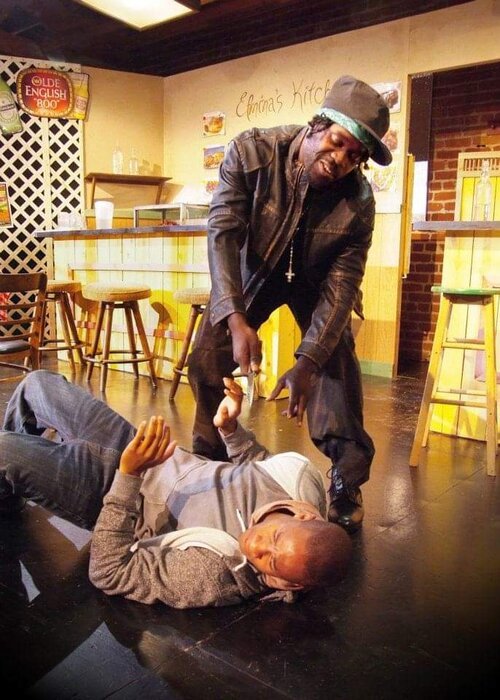

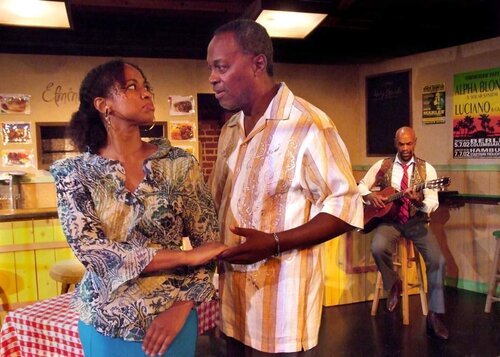

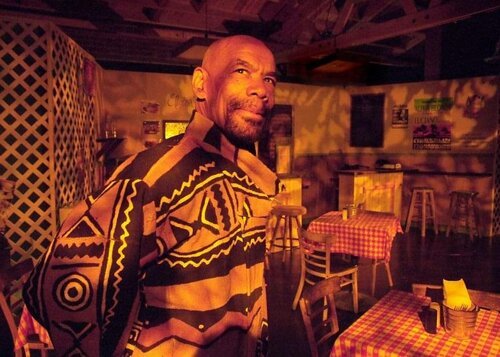

In 1979, he witnessed the Southall Riots, where clashes between anti-racist demonstrators and the National Front led to the death of activist Clement Blair Peach. It inspired his 1998 play A Bitter Herb, which follows a Caribbean family who are fighting for justice after a racist campaigner murdered their son. Elmina's Kitchen brought Black British theatre to national attention when he became the second Black British playwright to have a play staged in the West End in 2005.

Elmina's Kitchen¹ tells the story of a father and son in Hackney, navigating issues of education, crime and single parenthood. It is an example of what Colin Chambers refers to as a 'theatre of trespass', the countercultural phenomenon of Black British theatre that grapples with diaspora, intersectionality, migration, racism and much more².

Amongst cuts to art funding that is crippling local theatres and a sector struggling to rebuild itself after a pandemic, there has been a resurgence of Black British theatre. Black writers and actors were continually denied the space to perform and the opportunities to write and act.

What was intended to cripple Black British theatre instead birthed theatre companies and collectives, such as Yvonne Brewster's Talawa and Femi Elufowoju's Tiata Fahodzi. These organisations produced and sponsored Black playwrights and actors, unlocking talent and stories that otherwise would have been lost.

These collectives built communities with their audience, an element that Dugsi Dayz writer Sabrina Ali believes was paramount to the resurgence of Black British theatre. To her, 'audiences come as themselves and feel recognised', an unmatched feeling for a young and emerging playwright. Dugsi Dayz is a testament to the relationship between Black playwrights and their audiences, with its authentic and captivating exploration of Somali culture and female friendship. The play has returned to the Royal Court following a sold-out national tour, enjoyed an award-winning run at the Edinburgh Fringe and most recently won the BBC Popcorn Writing Award.

Dugsi Dayz also looks to the greats of the past to create stories for the future, taking inspiration from the classic John Hughes film, The Breakfast Club. Ryan Calais Cameron's For Black Boys… builds off Ntozake Shange's 'For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf' to create a beautiful blend of movement, music and storytelling. After three previously sold-out runs, Cameron and his stellar cast have returned to the West End. For Black Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Hue Gets Too Heavy builds a relationship between the playwright and the audience by responding to contemporary issues.

Through a captivating exploration of sexuality, men's mental health, race and the imagination of six young Black men in group therapy, Cameron builds a community with his audience. Tyrell Williams sought to address the loss of community in his hit play Red Pitch after noticing the football pitch he played on as a teenager was gone. Red Pitch follows three 16-year-old boys on a council estate in South London navigating community and friendship amongst the rapid gentrification of their area.

Sentiments of community are seeped into every corner of Black British theatre. The first generation included the likes of Errol John, Mustapha Matura and Derek Walcott, who carried rich stories from the Caribbean and placed them on the English stage. The Black Plays Archive, The Rendition and other platforms have worked to compile the past and present movement of Black British theatre. The new voices in theatre, such as Matilda Feyisayo Ibini, Benedict Lombe and Anastasia Osei-Kuffour, are thriving in a post-pandemic theatre resurgence. The community between playwrights and audience is generational—it is the shared understanding and expression of what it means to be Black in Britain.

¹Stills from Elmina's Kitchen (2012). Image property of Lower Depth Theatre.

²Chambers, C. (2011). Black and Asian Theatre In Britain: A History (1st ed.). Routledge.

³The first image carousel features a promotional still from Dugsi Dayz, property of Guy J Saunders and New Diorama Theatre, and a photo of Ernest Trimmingham in 1908, property of Illustrated London News Ltd. and Mary Evans.