Kendrick's Pop Out: Reflections on the Monumental Rap Beef That Made History

Sometimes, you gotta pop out and…

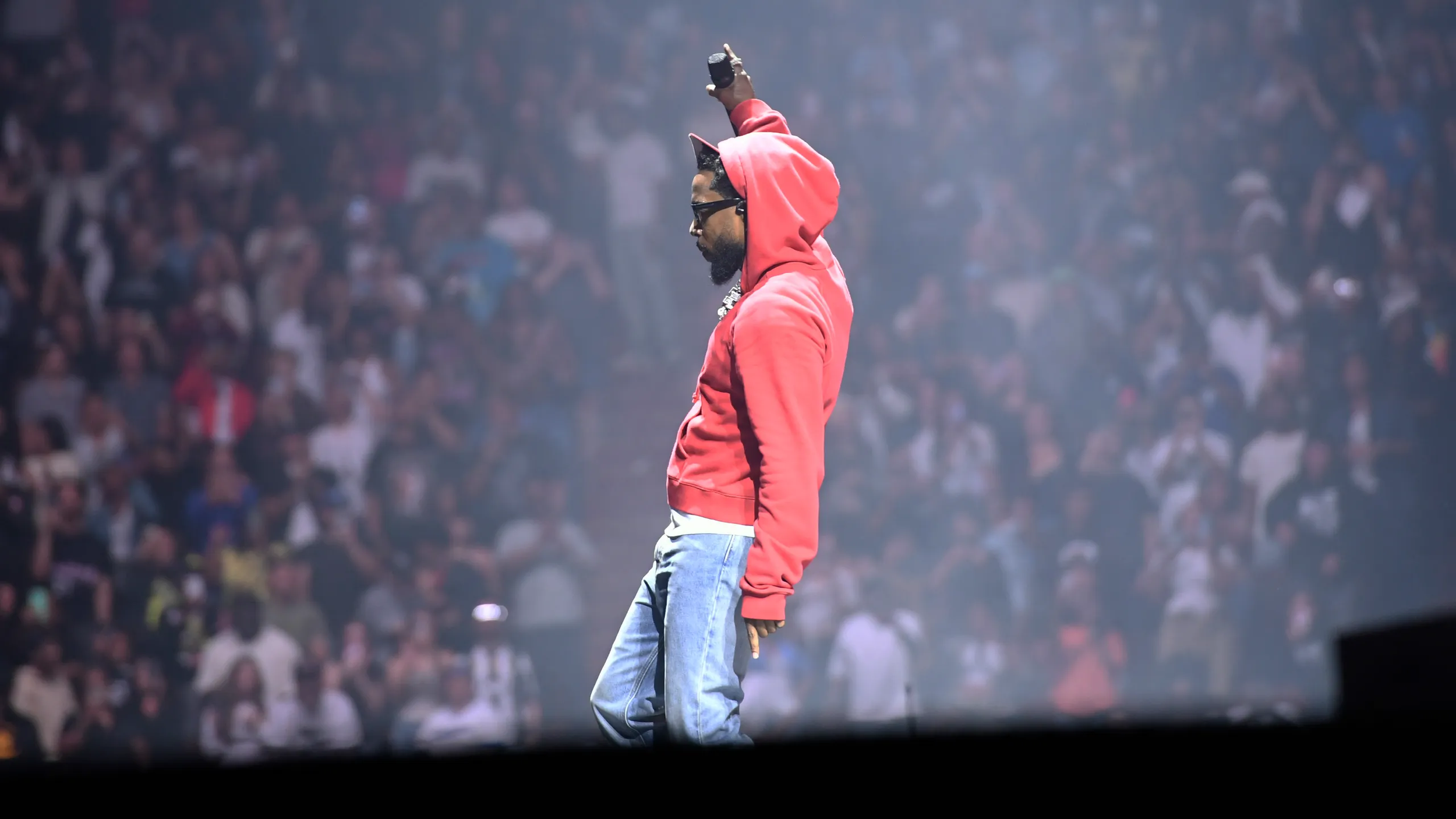

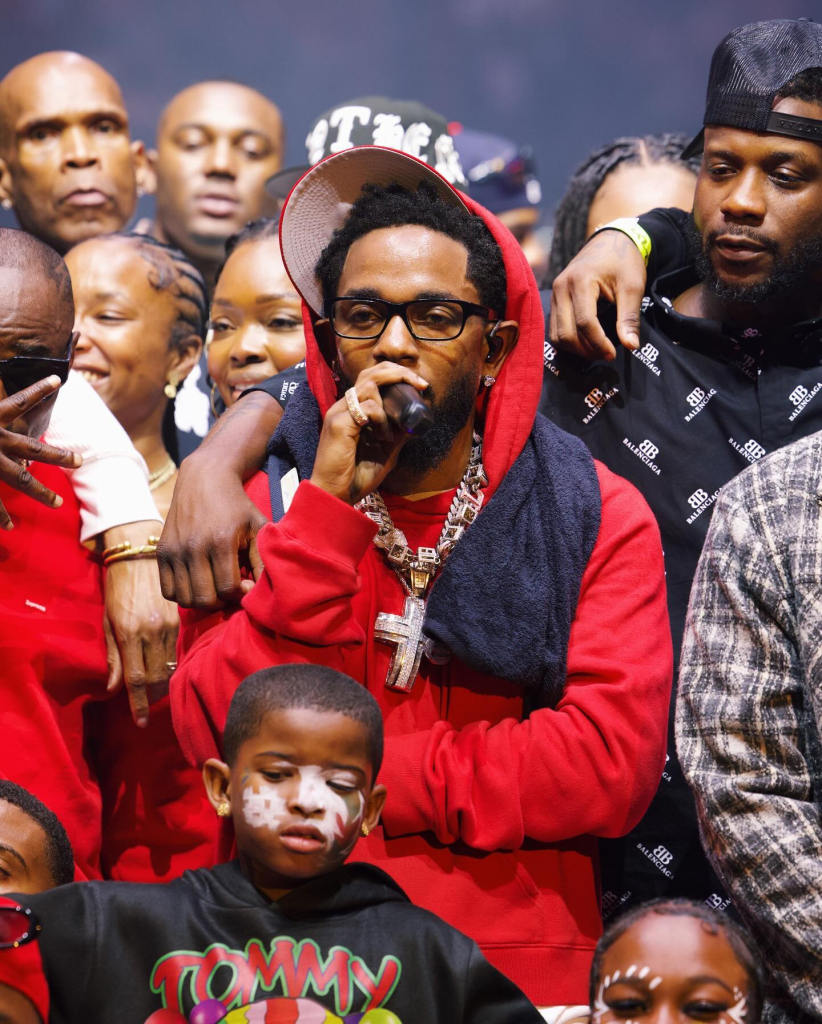

On Wednesday, 19th June, Kendrick Lamar hosted an unforgettable concert, The Pop Out: Ken & Friends, in Inglewood, California. This three-hour event took place on Juneteenth, a date that remains close to the beating heart of Black America. Kendrick held the show as an ode to the West Coast, uniting a myriad of local and national icons, platforming over 25 artists from the area and paying homage to the rap culture that raised him. Thousands of adoring fans attended, and millions tuned into the event online.

The guest list included Dr. Dre, Tyler, The Creator, Steve Lacey, ScHoolboy Q, Mustard, Ty Dolla $ign, LeBron James, Russell Westbrook and more, with special shout-outs for late legends Nipsey Hussle and Kobe Bryant, who were embraced in spirit.

Beyond uplifting the culture, the night also breathed life into the most explosive rap feud the industry has seen in years—it was Kendrick's first live performance since his highly-publicised rap beef with Canadian giant Drake. The dust had finally settled on the nine-track lyrical warfare, where questions of authenticity, identity and impact were thrown into the ring alongside a torrent of ugly accusations.

It's fair to say that Drizzy had been defeated; his final, unanswered offering, "The Heart Part 6", achieved little more than poor fan consensus and derisive memes. But what's a win without a victory lap? K Dot flaunted his success at The Pop Out, performing four out of his five diss tracks to a 16,000-strong audience who matched him bar-for-bar, opening with "Euphoria" and performing "Not Like Us" not once, but five times. Yes, five times—back to back—rounded off with a final instrumental version for good measure. Luckily for Aubrey, despite a star-studded guest list, he wasn't invited.

But this rap beef is bigger than them. Through the evolution of and discourse around the clash, a mirror was held up to reflect the state of hip-hop at large. It portrayed an image of rich culture and aggressive passion while adding threads to the long lineage of rap battle lore. However, we cannot ignore the darker undertones beneath the tribal fandom, slick beats, and witty rhymes.

During The Pop Out event, Kendrick repurposed the feud into a lens through which he could shine a light on the greatness of West Coast culture. This sentiment is born from a historical rap rivalry between artists from the East and West Coasts of the United States. Hip-hop culture (which encompassed rapping, street art, break-dancing and DJ-ing) was widely regarded as having roots in the South Bronx of New York City in the '70s, and East Coast rappers claimed this origin as a badge of honour.

However, by the late 1980s, hip-hop flourished on the West Coast, too, spearheaded by the likes of Compton's renowned hip-hop group, N.W.A. A focal point of the bicoastal beef was between the East Coast's Notorious B.I.G. and the West Coast's Tupac Shakur, two of the greatest rap legends in the game. The pair were initially friends, but crime and accusation led to them becoming sworn enemies, exchanging direct shots and subliminal blows in the booth and the media. They both met a tragic fate: Tupac and Biggie were murdered within six months of each other, aged 25 and 24 years old, respectively.

Although there is much speculation about the culprits and motives behind these fatal shootings, many believe that rap beef played a role in mobilising rival groups in violent circles of the East and West Coasts. Unfortunately, they are just two of the many fallen soldiers lost to street violence in the hip-hop world.

We must also remember 21-year-old West Coast rapper Mausberg, who was shot and killed in 2000 in his hometown of Compton, just one day before the release of his solo debut album. Or the East Coast's Big L killed at 24 years old in a drive-by shooting in his native Harlem. Such tragic tales remind us that the stories of the streets told in hip-hop lyrics are more than just entertainment.

Kendrick took the time to pay homage to those lost too soon during The Pop Out, emotionally stating: "We done lost a lot of homies to this music shit. A lot of homies to some street shit. And for all of us to be on this stage together; [this is] unity from each side of mother-fucking LA".

Rap beef can be viewed as a traditional part of hip-hop's legacy—this culture of audacious lyrical sparring sets rap apart from other genres. Some of the most notable hip-hop stars injected life into the culture by creating art from rivalry, rhyming and out-rhyming each other and wielding their words as weapons. Traditional rap warfare usually consists of consecutive diss tracks, straight shots and direct responses, and a key rule is that there are no rules, for better or for worse. The most famous showdowns include Ice Cube versus N.W.A, Ja Rule versus 50 Cent, and the culture-shifting rivalry between New York City icons Jay-Z and Nas.

The years-long feud between Jay and Nas really kicked off in 2001, when the pair released songs that would go down in history as some of the best diss tracks of all time. Jay-Z shot first in "Takeover," where he effectively called Nas a flop and said that his music was "garbage." Nas responded with the emblematic "Ether," bombarding Jay from all angles in what wound up to be one of the most scathing assaults in diss tracks in history.

The slam was so powerful that it created a new definition for the word "ether", refashioned to mean "to insult or humiliate personally". (Out of the 'Ether' | Merriam-Webster). Jay-Z clapped back with "Supa Ugly", twisting the knife in an assault as hideous as its title and shamelessly claiming that he was having an affair with Nas's then-girlfriend Carmen Bryan. The lyrics were so uncouth that Jay's own mother, Gloria Carter, called the local radio station Hot 97, saying that her son should apologise to Nas and his family. Like a well-raised child, Jay-Z did just that. But it wasn't the end of their battle—they had a few more years of beef in them before their reconciliation.

Embedding today's K Dot versus Drizzy beef in this colourful rap battle history gives texture to the story. But how did we get here? If you cast your mind back to 2011 when Kendrick and Drake collaborated on Take Care's "Buried Alive Interlude" or to 2012 when they spun gold on good kid, m.A.A.d city's "Poetic Justice", then the current civil war may feel like a fever dream.

But Drake is not new to the rap beef game, having clashed with the likes of Common, P. Diddy, Meek Mill and Pusha T in the past. With the cleanest of flows and sharp jabs bolstered by huge commercial success, Drizzy's repertoire of previous diss tracks is impressive, and nobody can take that away from him. Well, perhaps aside from Kendrick Lamar.

This time, after a decade of subtle shots and subliminals, the evolving rivalry between Drake and Kendrick hit boiling point. It all began with the J. Cole verse on Drake's "First Person Shooter", where he stated that he, K Dot and Aubrey were the "big three". Little did Cole know that he would awaken a beast: Kendrick took straight aim in his "Like That" feature on Future and Metro Boomin's album, WE DON'T TRUST YOU, stating "motherfuck the big three, it's just big me". Despite dropping a response to Kendrick in the form of "7 Minute Drill", J. Cole quickly apologised and retreated, clearing the way for the two icons to take arms in a head-to-head crusade.

Drake and Kendrick became embroiled in an exhilarating rap battle, beginning with hostile jabs and ending with the darkest allegations. The pair started off light, employing cocky sparring techniques and ultimately harmless low-blows: in the slick and abrasive "Push Ups", Drake mocks Kendrick's stature and relative charting deficiencies; in the blistering "Euphoria", K Dot hits back by mocking everything about Drake and claiming he doesn't make real music anyway.

Between those two releases, while impatiently waiting for a response, Drake disparagingly accused Kendrick of delaying due to the "biggest gangster in the music game" Taylor Swift's album release. In this diss track, "Taylor Made Freestyle", he also weaponises AI to recreate the voices of Tupac and Snoop Dogg, taking jabs at K Dot's legacy through artificial bars and unscrupulously taunting his opponent by imitating West Coast legends. Tupac's estate quickly took legal action, demanding that Drake take the song down.

Juxtapose this with Lamar's "6:16 in LA", which is also unavailable on streaming platforms, but this time at the hands of Kendrick instead of the law. The diss is laced with intricate layers and the "quintuple entendres" that Drizzy anticipated. In fact, the track truly was Taylor-made, reportedly produced by Taylor Swift's producer, Jack Antinoff. The offering is heralded as an unsung hero of the battle, and fans are still lobbying for a streaming release. However, withholding the track seems to be an active choice for Lamar, who mimicked his opponent by releasing the song exclusively on social media.

The feud took a sinister turn after "Euphoria"; perhaps the trigger point was when Kendrick accused Drake of not knowing how to raise his son. Drizzy responded with the seven-minute offensive, "Family Matters", alleging that Kendrick's son is the child of long-term friend and creative partner Dave Free, before damningly accusing K Dot of beating his fiancée. Kendrick's responding diss track was catastrophic—in "Meet The Grahams", he ruthlessly addresses Drake's son, mother, father and alleged secret daughter, accusing Aubrey of being a sexual predator and warning people to keep women and their families away from him.

The chart-topping "Not Like Us" then saw Kendrick doubling down on these allegations, openly declaring Drake to be a paedophile whilst rapping over an infectious beat, sealing the deal on what many saw as a clear victory, with Metro Boomin' adding salt to the wound with his irresistibly catchy diss track beat, "BBL Drizzy". Things were not looking good for the man in question.

In his final response, "The Heart Part 6", Drizzy absurdly states that he is "too famous" for the damning allegations to be true. In an even darker turn, he refers to Kendrick's self-professed history of being molested as a child, accusing him of projecting this trauma onto Drake through his lies. K Dot didn't grace him with a response; as "Not Like Us" swelled into an anthem, the battle had already been won.

In terms of globally dominating rival rappers existing at the forefront of the industry, Drake and Kendrick Lamar may be the final two of their kind. Therefore, some believe this is the last great rap battle we will witness. Now that the hype has died down, we're left with a reigning club banger and a nine-track-monolith to add to the tapestry of rap battle history, but where does our morality lie?

In this feud, direct accusations of paedophilia, misogyny and domestic violence were used as artillery, and the alleged victims, mainly women and children, were simply collateral—pawns on a battleground that they didn't choose to set foot on. How comfortable should we be with casually consuming lyrics that exploit such heinous topics without addressing them meaningfully?

With millions of fans around the world rapping every word of "Not Like Us" and stepping to the beat with carefree enjoyment, it's hard to reconcile the content of the lyrics with the elation surrounding them. Amidst hearty discussions about who's a better rapper and who won the war, serious discussions surrounding the gravity of the accusations seem to have taken a backseat. And there was hypocrisy on both sides—even Kendrick's mentor, Dr. Dre, who has been revered in the industry, has had to atone for his history of domestic abuse cases. Despite this, he was a star of the show at The Pop Out.

We may be slowly moving away from the homophobic slurs, ableist insults and overt misogyny peppered throughout rap bars of the last few decades. Still, perhaps we've simply exchanged the glaringly obvious bigotry for more subtle regimes—abuse, degradation, violence and trauma are still used as tools for "clapping back" in the name of rap superiority. So, have we really moved forward, or have we simply changed the mechanism by which we use oppression as a weapon?

Rap warfare is many things at once: a playground and a battlefield, a mode of fun and a question of morality; both entertaining and alarming at the same time; it unites, and it divides us. During their careers, Kendrick Lamar and Drake have immensely impacted the modern musical landscape.

In the wake of their monumental clash, we can appreciate how the music scene was ignited, with onlookers across the globe waiting in anticipation for each new chapter to unfold. But in our quieter moments, we must turn down the volume and reflect on hip-hop and rap battle culture at large, daring to consider where our morality should lie within them. Although music is supposed to entertain and be enjoyed, it should also empower and inspire—or, at least, it shouldn't do the opposite.

We must allow light to remain at the core of rap, if only to allow the genre to exist and evolve with the world around it.