From Eye Candy to Icon: Unpacking the Role of the Video Vixen in Hip-Hop

Women in hip-hop have taken centre stage, giving a voice to the vixen and righting the wrongs of a testosterone-fuelled landscape.

Hip-hop, both as a genre and cultural movement, has long been synonymous with clever wordplay, extreme displays of ostentation and boisterous representations of masculinity. Seldom given its respect, however, is the video vixen. These captivating women, who dominated the music videos of the 1990s and 2000s, were once seen merely as eye candy, relegated to the background of a male-driven industry.

But times have changed. Today, these vixens are now stars in their own right, with female rappers and musicians combining beauty, talent and sex appeal into one single undeniable force.

Female hip-hop artists now cleverly play the role of both video vixen and artist to maintain their spot in a 'man's world' and command attention on their own terms. During her rise to rap stardom, Nicki Minaj was often referred to as a video vixen and fought to earn the respect of her male counterparts. Through her warranted success, the tide started to turn, and the vixen had shifted into the icon herself.

“I’m Nicki Minaj, bitch! It’s Barbie, bitch! (...) Nothing else matters. Niggas know.”

The emergence of the modern video vixen can be traced back to the 1980s alongside the rise of hip-hop. But if we cast our minds even further back, we find an early prototype in Josephine Baker, the legendary American-born French performer known as the Black Pearl or Black Venus. She is forever remembered as the flapper-era showgirl in her characteristic wearing-nothing-but-a-banana skirt, pearls and short, slick hair.

While Baker was not featured in a music video, she could be considered a trailblazer as the early version of what we would now call a video vixen. Her career garnered major fame and international influence for her knack for performance, entertainment, provocative costumes—particularly audacious for the time—and, importantly, for her sex appeal.

Baker's persona, particularly in that iconic banana skirt, was inspired by the character Fatou-Gaye, a personification of primitivist fantasies of an African woman in the French novel Le Roman d'un Spahi by Pierre Loti. Concurrently, during the Harlem Renaissance, a creative explosion and cultural shift occurred during the 1930s, and performances like Josephine's were widespread. This specific performance style and genre was called the 'Black Vaudeville', a Black style of burlesque comedy, dance and entertainment blended into one.

Yet, under the backdrop of the Jim Crow-era spanning from the 19th century, the Jezebel stereotype—the notion that Black women were promiscuous, seductive and sexually insatiable—inevitably became somewhat entrenched in society. The impact of the Jezebel is seen not only as a stereotype but as a meta-stereotype, which describes how women in entertainment will respond to this stereotype and impact how they perceive themselves.

Over time, as sexuality, media, and entertainment became so closely interwoven, the incorporated Jezebel meta-stereotype returned to the cultural forefront. With this knowledge in tow, relatively subdued or theatrically focused performances became increasingly sexualised. Hence, music videos' set dressing and furniture from the 1980s and onwards evolved to form our modern understanding of the video vixen.

The Video Girls of the 1980s

Amid the rise of hip-hop, video girls, dancers, or performers were a music video staple. MC Hammer's hit "U Can't Touch This" exemplifies this, toeing a subtle line between the video girls starring as models, exuding a certain sex appeal to dancers, helping to bring a jolting energy to the visuals.

Sir Mix-A-Lot's "Baby Got Back" shows a more sexualised depiction of Black women as the object of sexual desire alongside male rappers. The beginning of the music video features two white girls criticising the girl in the yellow dress: "She looks like one of those rap guys' girlfriends", demonstrating the way that video girls were intrinsic to the genre and the production of hip-hop music at large.

As such, initial portrayals of Black and Brown women in these music videos were confined to specific roles spanning across hundreds of popular rap videos, and began rousing major criticism from feminist groups in a historically Black college, Spelman College. Namely, Nelly's polarising 2003 song "Tip Drill", remixed from his single "E.I.", garnered scrutiny for being extremely misogynistic and disrespectful towards women.

This was not only owing to its crude depiction of women performing sexual acts for money thrown by the fistful, highlighting this 'hoe' and 'trick' dynamic but also as the slang term 'Tip Drill' referring to a woman who has an 'ugly face' but a 'nice body'. While these instances of extreme objectification were common, other videos achieved this far more subtly, giving rise to the video vixen mantle.

The Video Vixens of the 1990s and 2000s

As children of the 2000s look back, video vixens are celebrated in the archives as beautiful and iconic figures of the era. This combination of nostalgic reverence and enthusiastic aesthetic appreciation has led some down memory lane. With the help of TikTok, songs like Pharrell Williams's "Frontin'" made it back into view. With its glowy and slightly lower-res yet still strikingly colourful and sharp style of camerawork, it urged many to wander back to the video vixens and what they may be doing now.

Melyssa Ford. Karrine Steffans. Jeannette Chaves. Lauren London. Blac Chyna. Amber Rose. Bernice Burgos—all very prominent 'it girls' of the video vixen era. The fact that we're likely to recognise these names highlights their essential part in hip-hop.

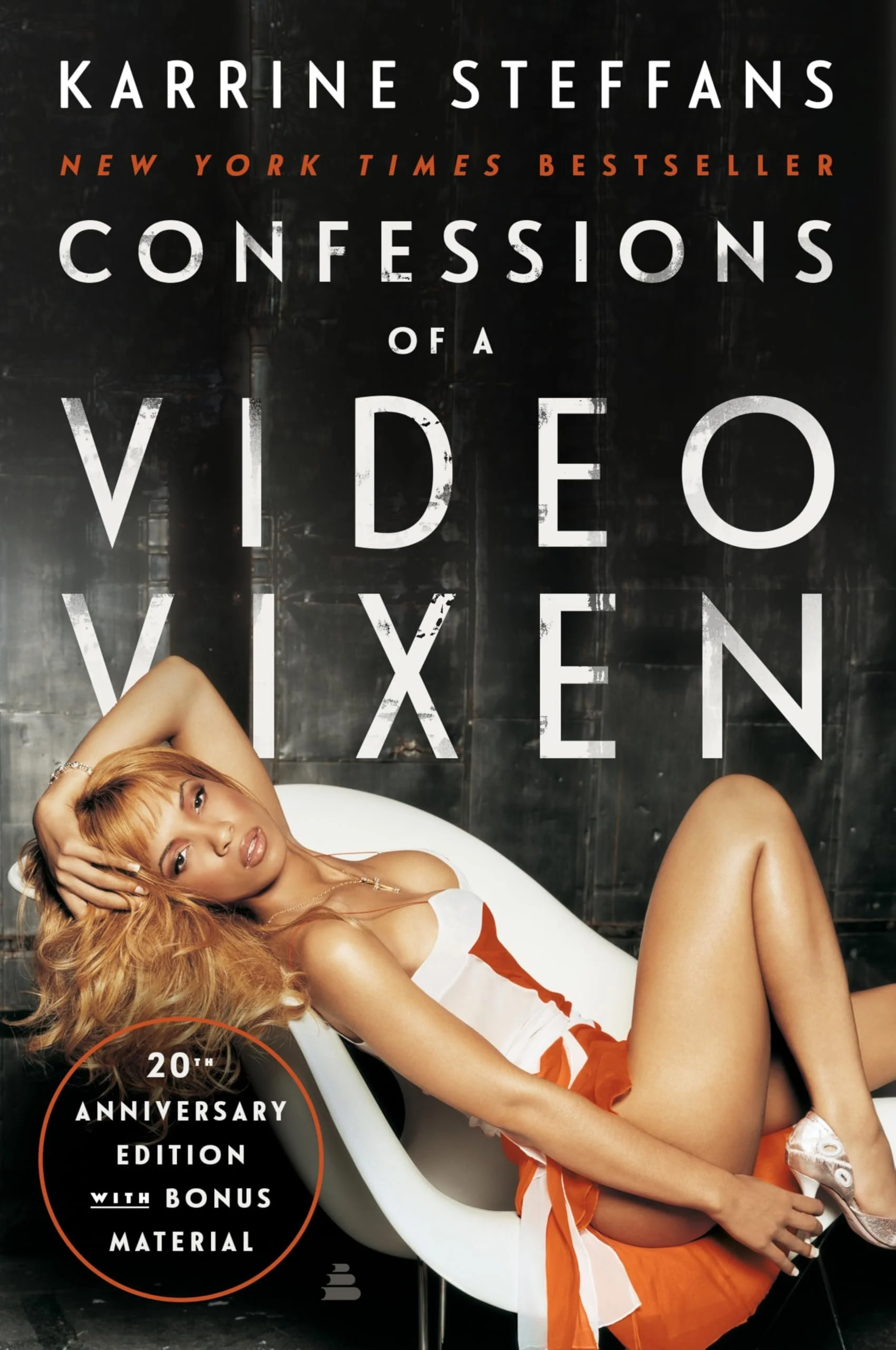

However, while having a significant impact, they all led to very different experiences. Karrine Steffans' 2005 book, Confessions of a Video Vixen, is a tell-all autobiography that unveils the highs, lows, and harsh realities of life as a video vixen, ultimately making her the talk of the town. Steffans (now Elisabeth Ovesen) recounted her time being sexualised in the male-dominated sphere, traversing difficult and vulnerable situations and even triumphs in her sexcapades with prominent rappers who were named and sometimes also unnamed.

While many fixated on the glitz and glamour aspect of life, Steffans' memoir sought to reflect upon her difficult childhood as well as instances of sexual, drug and domestic abuse. "A lot of women have unrealistic views of this part of the industry", says Karrine during a tense interview on Tyra Banks' talk show. Though it had gained sensational attention, Karrine's intentions for the book were to serve as a cautionary tale for other young girls who yearned to be part of the in-group she once also dreamt of being a part of:

"Where young girls aspired to be models and ballerinas, they now aspire to be hip-hop video girls. The next hot girl in the hottest artist's video. Having lived that life, it's not all it's cracked up to be."

While she wrote earnestly about her experiences of abuse, a lot of readers were solely gripped by the name-dropping. But she reaffirmed on Tyra Banks' show that "The book isn't about sex, rappers, or hip-hop." Coincidentally, Karrine's oeuvre was somewhat of an omen symbolising the end of the video vixen era as we once understood it. She had shone the spotlight onto all the ugly, lonely and difficult parts of the industry—what it is like to be sexualised, objectified, commodified, and exploited.

While her experiences were shocking, they were not exceptional. She expresses that many young girls—many from underprivileged backgrounds—often fall into this trap. However, throughout 2007 and 2008, she was a keynote speaker at many university campuses across the US, including for her promotional tour following the significant success of her book.

“I realised recently that I’m surrounded by young women who have never had a sexual revolution. So I became almost this figure, this Joan of Arc [for them].”

At this time, Karrine received major flack for appearing to be proud of who she is, not cowering in shame, choosing instead to speak out and daring to be seen. Many slut-shamed her, choosing to focus on her sleeping with many industry giants instead of scrutinising the very mechanisms of the industry that allow young girls and women to be sexualised and exploited for profit. We could even call it a pseudo-capitalistic-pimping of the woman within the microeconomic landscape of Hollywood and its video vixens.

Following this 2000s-obsessed age we are in, especially over the pandemic era currently, many people look back to the beautiful girls who represented all the glamour, fabulousness and appeal of this bygone era of hip-hop.

'Where are they now?' line-ups were being made on social media as people kept up with the girls they had once all seen in music videos past. Similar to Karrine's message in her book, some of them ended up in the throes of addiction, and some succumbed to sickness. Still, some also thrived and continued to live relatively everyday lives as influencers, models, actors, or even regular 9-5ers alike—both in and out of the limelight.

According to Revolt, Melyssa Ford, a Toronto native and York University alumni, is now a co-host of the Joe Budden Podcast as of 2022. Karrine Steffans has continued to author many other books about her experience as a video vixen and relationships. Buffie "The Body" Carruth created her own clothing line, Brick Built Apparel, and authored her book Vixen Icon (The Buffie The Body Story).

“It’s safe to say that being a video vixen is something that I eventually graduated from.”

…Has the Video Vixen Become the Artist?

The artist being both the musician and the video vixen simultaneously isn't a completely foreign concept. Many rap icons like Lil' Kim and Foxy Brown have become quite enmeshed into the fashion industry. Foxy Brown, in addition to her immense lyrical and musical talents, became a muse of John Galliano and was celebrated for her uniquely fabulous arrogance.

Lil' Kim is renowned for her iconic '90s looks sported on the red carpet and in her music videos and her fair share of collaborations and huge designer co-signs, from Marc Jacobs, Giorgio Armani, and Donatella Versace. She became a fashion fixture, incorporating style, music and Hollywood stardom into her persona. As early architects of the modern-day female rapper persona, they blended the music, bold lyrics, audacious fashion choices, attitude, beauty and sexiness all into one.

The star-studded music video to her song "Not Tonight (Ladies Night Remix)" featuring Missy Elliott, Da Brat, Left Eye, and Angie Martinez exemplifies the phenomenon. In addition to the features on the track, the music video also included cameos from other industry giants, including Mary J. Blige, Queen Latifah, SWV, and Xscape, all celebrating their collective greatness and solidarity.

While it significantly shaped the female rap landscape, many women in the genre still sought to earn the respect of an industry dominated by men—prioritising their lyrics over their appearance. This meant many rap girls chose to sport baggy Tommy Hilfiger jeans, big and bold styles with masculine silhouettes maintaining a chic boyish charm like Da Brat and Missy Elliott.

Over time, this persona became increasingly prevalent. By the end of the 2000s, Nicki Minaj had emerged as the argued successor to Lil' Kim (a controversial opinion) and, similar to her, had adopted this new all-encompassing video vixen-esque persona. Here, we observe the shift from object to icon, gaining everybody's respect through both her raps and her looks.

Shifts in Representation and Perception

Today, the voluptuous, hourglass-shaped seductress with amazing musical ability and charm is a staple in the female rap scene today (even R&B artists alike), with big-name artists like Latto, Doja Cat, Cardi B, GloRilla, Megan Thee Stallion, Sexyy Red, Ice Spice and Flo Milli all making their mark and adopting this aesthetic. We see this in the casual name-dropping of designer brands in their music, provocative and boastful lyrics about their sexual prowess, their flawlessly painted faces and fabulous wardrobe and styling front and centre in their own music videos.

The image of the 2000s video vixen became less prevalent and less visible as more female artists conformed to this new norm following the 'sex sells' principle. However, now I believe female artists are commodified under this more evolved version of the video vixen. The beauty standards, expectations, and capitalistic commodification of the female form haven't just vanished along with the video vixen—they merely evolved to the shift.

Footage of Ice Spice's performance during Miami's Rolling Loud festival in 2024 can even serve as funny symbolism for how tired women in the industry must be. Many X/Twitter users speculated and attempted to recontextualise this moment as a broader symbolism of what female artists tolerate in this industry and the resulting fatigue—particularly in performing, commodifying and selling this image of a sexy and desirable artist to successfully market their music to an easily bored audience.

Video Vixens as Cultural Icons

In the evolution from eye candy to icon, the role of the video vixen in hip-hop captures both the power and complexity of the genre's engagement with femininity, beauty, and talent. Initially confined to the sidelines, video vixens of the 1990s and 2000s commanded attention yet remained peripheral to the male-dominated stage.

Today, however, female hip-hop artists are reclaiming this space, blending the allure of the vixen with the artist's authority to create a new, empowered identity. Figures like Nicki Minaj and Cardi B exemplify this shift, embodying a persona that balances sexuality and artistry with unapologetic confidence. This metamorphosis has a profound impact, signalling a step towards autonomy for women in a male-dominated genre.

The modern vixen-turned-icon challenges these limitations, reshaping hip-hop's landscape into one that celebrates and respects women artists' talents and shrewd skills while highlighting ongoing issues of objectification and beauty standards.

As hip-hop continues to evolve, the dual role of artist and vixen brings both opportunities and pressures, underscoring the need for further conversations on representation and respect within the industry.

Ultimately, the journey of the video vixen—from background player to central figure—reflects hip-hop's complex, dynamic dialogue with femininity and empowerment, leaving a lasting legacy that both critiques and celebrates the genre's history and future.